A Barn Abroad: Early Memories Of Norway

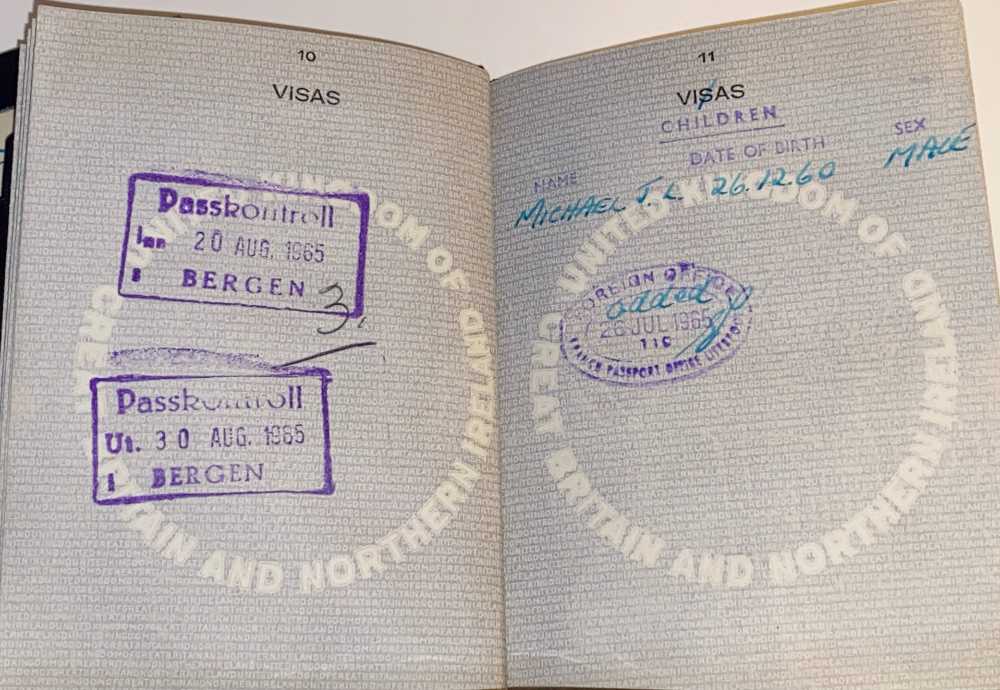

I’VE BEEN TO NORWAY TWICE, both times as a child. The first time was in August 1965, when I was four years old. I know the date because it’s stamped in Mum’s and Dad’s passports which, in a way that was utterly typical of my parents, they retained religiously; there is still a cache of such materials among their effects in what was the family home, to which I returned in 2020.

Naturally, my childhood recall from nearly 60 years ago must be treated as partial at best, though I think not as completely unreliable. I have mostly snippets from the 1965 trip, though I do particularly recall being taken for a very Norwegian ice cream, which came not in the crispy orange cone I was familiar with from Mr Whippy, but in a sort of rolled crepe that would much later appear on the UK market in the form of the Walls’ Cornetto.

Other than fragmentary impressions of the ship―a Fred Olsen line vessel that sailed regularly between Newcastle and Norway, either the Blenheim or the Braemar―I don’t remember much about the crossing. I was impressed, though, by how everything on board was badged and branded in blue and red, much more colourful than the only equivalents I knew of at that age which were the symbols and livery of British Rail.

Mum and Dad had, shrewdly, taken steps to provide activities to keep me occupied during the crossing of the North Sea. At the time I was fascinated by Doctor Who, having only recently seen the programme on the television at my aunt and uncle’s house. Dad had taken me to Boydell’s toy shop on Elvet Bridge in Durham and allowed me to have three miniature Daleks; each one just over an inch tall and with a ball-bearing in the base so they could be scooted across a tabletop in a convincingly Dalek-like manner.

The model Daleks were supplemented by a sketchbook with coloured pages to draw on and a set of felt pens to draw with. The cover of the book might even have featured an illustration from the Peter Cushing film Dr. Who and the Daleks, which I think I was taken to see shortly after the Norway trip. I filled the yellow, green, blue, red and orange pages with early impressions of Daleks, usually with copious death-rays flashing from their exterminating appendages. The ball-bearing Daleks are collectors’ items now and change hands for upwards of £80, an unlikely sum compared to the 1960s price of one shilling and six pence.

The excursion was a special summer holiday decided upon because Dad had been travelling to Norway to conduct field trips as part of his research on blackflies, pests that can be detrimental to livestock. No doubt the old boy was combining a family holiday with the secondary purpose of scouting out locations with an eye to further research, as proved the case on a second trip to Norway.

The Bergen vacation was more relaxed and my sister, then fourteen, was also with us. Still, the outings and sightseeing, such it was, centred firmly around the old man’s interests and preoccupations. Principal among these was a passion for railways and in particular steam locomotives. At some point he contrived for us to have a ride on a steam train, no doubt carefully planned well in advance. I have very strong visual recollections of parts of that day, especially a sunlit afternoon at an old-fashioned clapboard station. For years I thought I’d never be able to find out where that station was, but with the search capabilities of Google Street View, I successfully managed to identify it as what is now known as the Old Voss Railway, and the station house was the one at Arna, not far from Bergen.

Being August it was high summer and the day of the rail outing the weather was spectacular. The sky was a cloudless blue and the sun was bright. From the windows of the carriage, I could see we were moving through a landscape bordered by mountains and there was snow visible on the distant peaks. Nearer to hand there was more recent snow melting off the trackside trees as the locomotive pulled us higher and higher.

After a while — perhaps it was the end of the line and time for water and refuelling — we got out at a station. It was a sleepy sort of a place and there wasn’t anyone about. The yellow station house was wooden and, like the railroads in Westerns, there wasn’t a platform, just an extension of the gravel ballast that supported the track, and passengers had to climb a short ladder to get up and down to the train.

There must have been a while to wait for the return journey because during the layover I had a bit of a poke about, as impatient and bored four-year-olds are wont to do. For some reason there was a standpipe and tap at the end of the station area and around the tap had been left a collection of plastic toys including a seaside-style bucket and spade. I amused myself by filling up the bucket and distributing the liquid between sundry of the discarded receptacles that were conveniently to hand.

I’ve little recollection of anything much else beyond the pellucid quality of the light. The place seemed dreamlike in its modest perfection. Indeed, my retained impression of Norway is of a place as picturesquely beautiful as Switzerland in a 1950s movie shot in Technicolor, serenely ordered and calm. Everywhere was neat, cared-for, and tidily efficient.

The other thing I remember from August 1965 was meeting a boy called Clive in the foyer of the hotel. The pound to krone exchange rate must have been favourable, because Dad was able to put us up in a hotel that was very much swankier than anything we could have afforded at home. In the foyer was an ornamental pool with a fountain. Clive was sitting beside this pool making paper boats and floating them on the water. I was fascinated, and Clive showed me how to fold the paper to make a boat.

I spent perhaps ten minutes in the company of Clive, who was much of an age as myself. I retain an impression of a pleasant-looking blonde boy who made me think of the illustrations of Christopher Robin in the Pooh books, which were very much central to my existence at the time. It’s often caused me to wonder why I still have a memory of that fleeting acquaintance, and who Clive is or was. It seems so incongruous that I remember his name sixty years later. Other than the paper boats there was nothing intrinsically important about the encounter that could have caused it to have lodged so securely in my mind.

Of the second trip, in July 1967, I have more coherent memories. This time we were bound for Oslo, not Bergen, although I think we might have berthed at Bergen before completing the journey to Oslo. Inevitably, given that I was only six, the order of events is sketchy and incomplete. The journey must have started with a train trip to Newcastle, although it’s just possible that Dad might have had a friend or colleague drop us off; we certainly wouldn’t have had a taxi all the way. I do remember the departure lounge, for want of a better word, it was more like a station concourse, where we waited to board the boat.

As a treat I was allowed a copy of The Eagle comic; usually considered too advanced for a six-year-old, it was more the preserve of my older brother Peter, who had quite a collection of Eagles that I was allowed to look at only very occasionally. However, I was distracted from perusing the adventures of Dan Dare and the Mekon by the sight of a man rolling a cigarette. Not in itself unusual, saving only that the man in question had only one arm. With considerable panache―perhaps deliberately affected to impress a junior spectator―he proceeded to open his tobacco pouch, take out a paper and carefully position it on his thigh. He then contrived to sprinkle tobacco into the groove of the paper which he lifted to his lips to moisten the adhesive gum. Then in one supremely dexterous movement he rolled the cigarette over his thigh with the palm of his hand to produce a perfect cylinder which he promptly placed between his lips and lit. I was hugely impressed.

The on-board accommodation was a good deal less salubrious than on the first trip. We were in Third Class this time (perhaps the exchange rate wasn’t so good) and I was in a cabin with Dad, and I think, another bloke. I’m fairly sure Mum was off separately. Perhaps Third Class was all that was available, perhaps the ship was older, or Dad had left it late to make a booking. Either way, there was no porthole and the series of passageways, corridors and companionways that had to be negotiated to move around the ship I found endlessly confusing. I didn’t like the food on board and felt seasick quite a bit of the time. I think we were three nights on board; it certainly seemed like a long trip to me.

Such impressions as I have retained of Oslo are that I found it like a storybook city, resembling places I had read about and seen illustrated in books. Doubtless I couldn’t have formulated it into a coherent thought at that age, but what I was learning to recognise was that the different styles of architecture, the variant street furniture and signage, even the dress of the natives, marked Oslo as a properly European capital city, bigger, brighter and prettier than anywhere else I’d been―which was nowhere very metropolitan. My paltry comparisons at that age would have been Sunderland and York.

Our next destination was the village of Koppang, some three or four hours to the north of Oslo. Thence to a motel―a novel concept in 1967 ―and a seter a couple of miles from the motel at Renåvangen where Dad was due to join a group of scientists who had set up for a summer of field research. My impression is that the group were international, but from English-speaking backgrounds, including at least one woman, and all were involved in field studies with some environmental/ecological/ecosystem dimension. The one member of the crew I do remember is Victor. He was younger than my parents, perhaps mid 20s, and might have been doing a PhD or some postdoc research.

Who’d set the field station up or why, I’ve no idea. I’m pretty sure it wasn’t Dad’s doing; rather he’d found a way of hitching his research wagon to something that was already going on. Neither do I know why the group had come to be based at Renåvangen. Possibly there was some connection to academia in Norway, but I don’t think I ever really knew―it was simply one of Dad’s bits of entomological research and Mum and I were getting a holiday out of it.

Koppang was a small place in 1967, and it doesn’t look to be much bigger now. The train journey to reach it was a long one for a six-year-old already tired after crossing the North Sea. I probably slept at least part of the way. One feature of Norwegian trains did compel me, though. At the end of every carriage in the space between the entry and exit doors there was a water dispenser and a rack of cone-shaped paper cups attached to the wall. It tickled me no end to go and get the tiny conical cup refilled at regular intervals.

The motel was twenty kilometres out of town and reached by a road that wasn’t much better than a gravel track. We approached through a pine forest which then gave onto a moorland section leading to a small bridge, and just across the bridge the motel nestled by the side of a stream, surrounded on three sides by trees. The site consisted of two main blocks with a large gravel parking area in front. The cabins were in a one-storey wooden building at right angles to the road down the left-hand side. Facing the road across the parking lot was the main building. This housed reception, a restaurant/dining room and, I later discovered, a laundry facility.

Another smaller block, not much more than a glorified hut, was among trees to the right at the back of the lot, and this was the accommodation for Hazel and Anna Marie, who worked at the motel and who would become my babysitters, not to mention my earliest crushes. I think there was a third girl, but I only really remember Hazel and Anna Marie. I liked them both, but it was impossible to have a favourite because it was like having to choose between the blonde and brunette in Abba: they were both gorgeous in my besotted eyes.

The proprietor of the Renåvangen motel was a big friendly bear of a man who presided over breakfasts and couldn’t understand why I turned my nose up at gjatost and crackerbread. Our cabin was about halfway along the row and at the back looked out over the stream to the trees on the far bank. Dad―ever the naturalist―spotted that there was a dipper active on this section of the river, and I’d spend hours watching the small bird with its characteristic repeated knees-bend squat.

Most days Dad would set off to the seter after breakfast. Quite often Mum and I would follow a little later. It was a good walk, perhaps two-and-a-bit miles, and tough going uphill in hot sun. The way was a rough track through pine woods with occasional vistas across a valley to more distant woods. Masses of ants moved in an endless column down the side of the track, millions of them, and between the trees could be seen large brown anthills, four or five feet high and made of pine needles.

At the seter there wasn’t much to do. Occasionally Dad would take me over to see where he’d set up his sticky traps. These were four-legged wooden contraptions something like a sawhorse but bigger, to resemble the shape of the local cows. The fake cows were painted with a form of non-drying bitumen so that insects landing on the dummies to bite the ‘cow’ would be caught. Lewis would then count the insects and establish which species were represented. It was something to do with estimating insect population sizes and the intensity of their parasitism on livestock.

If I remember correctly the female blackflies needed a blood meal to reach sufficient maturity to lay eggs. It was grisly stuff, and never mind the livestock, humans got bitten as well. We attempted to fend off the irritation of midges etc. by liberal application of a fly repellent liquid that had a wonderfully aromatic smell. It only seemed to work to a limited degree, and the flyblown atmosphere of the countryside around the seter made it a not particularly attractive destination. The facilities out there did little to encourage repeat visits either. The netty, as I knew it in northeastern parlance, was a wooden outhouse across the track from the seter house. The plank door had a heart-shaped hole. I think so you could see if the throne was occupied and thus avoid barging in on an incumbent. It was a chemical toilet and stank abominably.

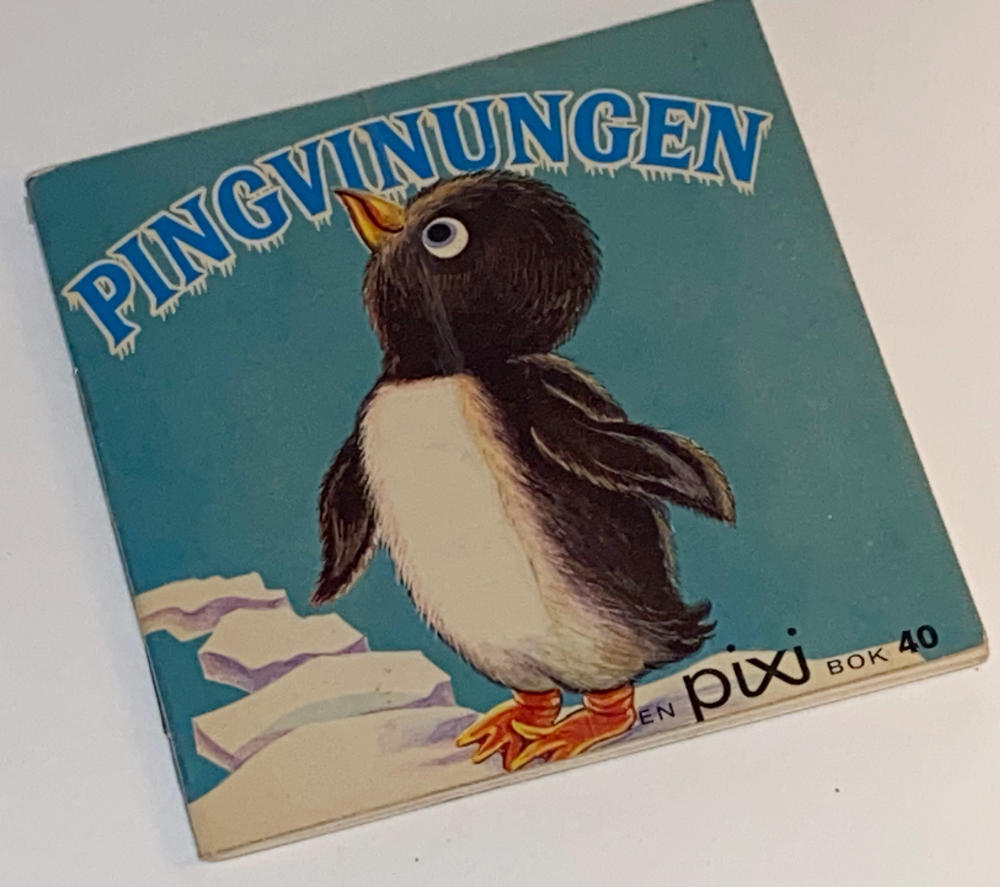

Between times we had occasional outings―a trip to Koppang was an event, and I was treated to a Norwegian picture book about a Penguin called Pingvinungen. I tried to translate it with Dad’s Norwegian phrase book, but even with the assistance of the adults it proved too difficult. Another time the gang from the seter took off to a nearby lake. It might have been a public holiday or perhaps just a fine Saturday. There was a sandy beach at the lake and a small crowd were doing beach-type things including swimming in the lake.

Several times Mum and Dad handed me over to Hazel and Anna Marie in the evening. I’m not sure if they were dining with the staff of the seter, out for a drink, or just getting some time to themselves, but I loved being made a fuss off by the girls. They were probably around eighteen to twenty and made a bit of a pet of me. I’d be allowed to sit up with them, although what we did I have no idea since they had minimal English and I had no Norwegian at all. Then they put me into one of their beds until Dad came to collect me and carried me back to the cabin asleep, or half asleep.

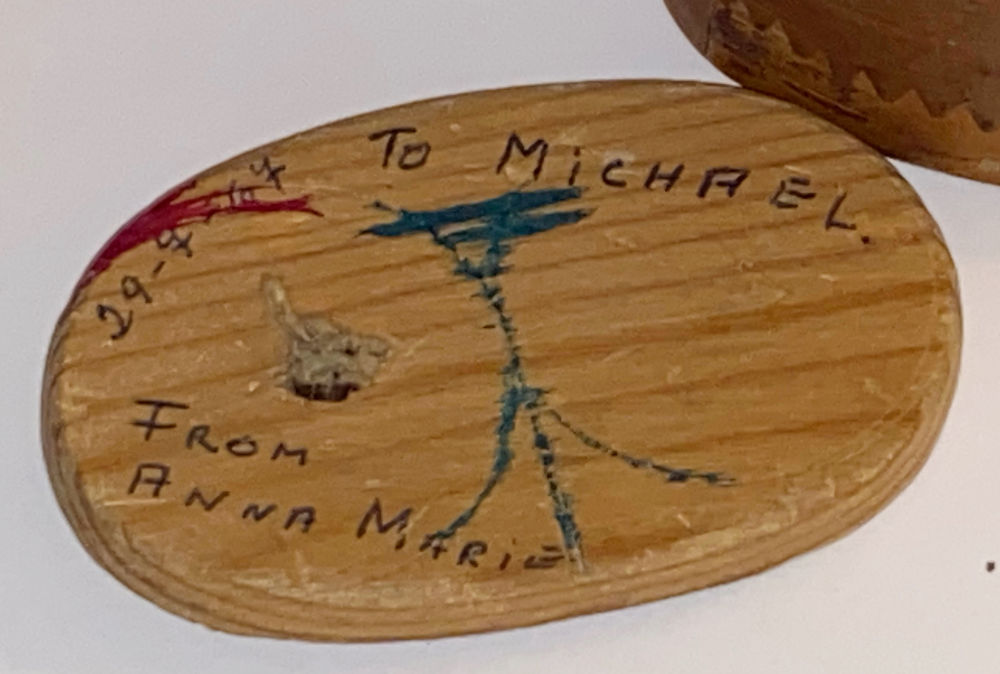

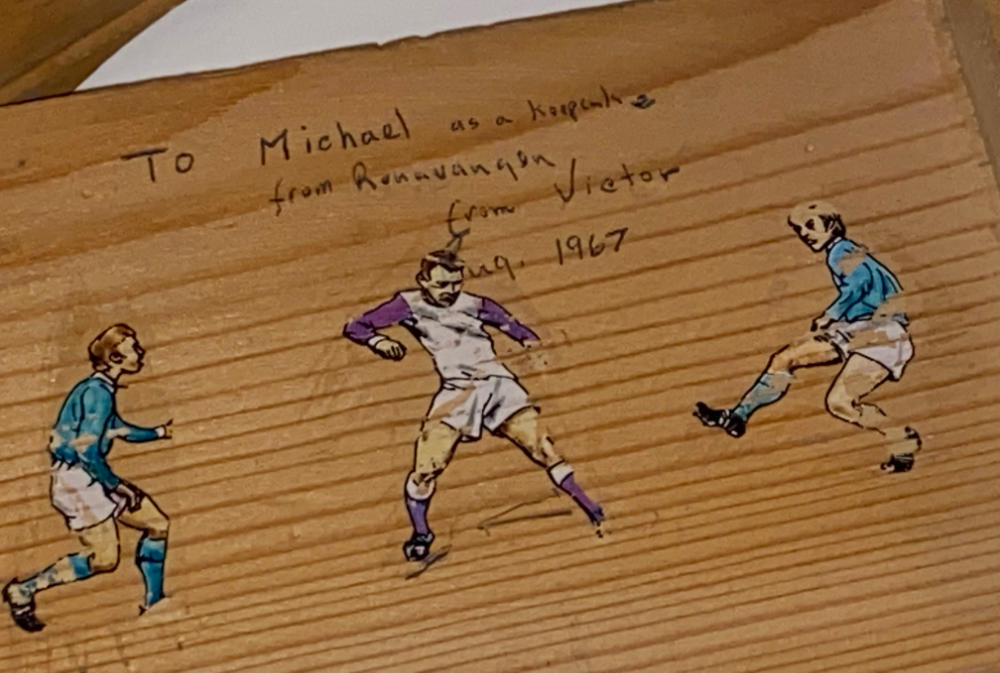

When the time came that we were leaving there was a Midsummer bonfire and celebration at the seter. It was exciting to be allowed to stay up, and the bonfire was a substantial one, built on some rough ground away from the trees so sparks wouldn’t spread. The following morning Hazel and Anna Marie gave me small presents―mementoes from the motel souvenir shop―an oval bark box with a wooden lid that they had written on, a plaque with a picture of Koppang on it, and Victor gave me another wooden trinket box from the souvenir shop with a postcard photo of the motel stuck on the lid. I was delighted with all three gifts and still have them.

I don’t remember the train journey back to Oslo, but there must have been spare time available because we visited the Fram and Viking Ship museums as well as Frogner park. I was most impressed by sculptor Gustav Vigeland’s tower of writhing figures at the centre of the park. There were a lot of grey squirrels and I spent fruitless minutes trying to persuade one to take a nut from me.

I retain nothing about the journey home apart from being bought a novelty biro with which to draw―I drew all the time so pens and paper were an easy way to keep me occupied. The pen was a fat clear plastic cylinder that contained red, orange, purple, blue, green and black biro tubes that could be clicked from one colour to another. I drew a lot with that pen, and it survived the journey because I was still drawing with it months later.

Years ago I did try to find Renåvangen online, but I’d misremembered the spelling. This time, I was able to find it. It’s now a drug rehabilitation facility and the river it stands beside is the Fugga. My online searches also produced names for the lake I remember bathing in, Storsjøen Rendalen, and revealed the details of the 1965 steam train journey. I even managed to identify a likely candidate for the swanky hotel in Bergen; it might well have been the Hotel Rozenkrantz.

Lewis died aged 83 nearly twenty years ago now, and Alice died nine months ago, so I can’t draw on their memories of the Norway trips to check the accuracy or otherwise of my impressions. Nor can I get answers to the questions about missing information and actual locations that Dad would have remembered precisely. My sister has only a hazy recollection of the 1965 trip, but she did remind me that we were bought Norwegian sweaters in Bergen which we both rather liked. Jen also said that the North Sea crossing back to Newcastle was horrendous, but I have no memory of that at all. I probably slept through the rough seas.

As I’ve been reminiscing about the Norway trips it becomes ever clearer that the second trip wasn’t really much of a holiday at all, at least not for Mum and me. The old boy had, with absolutely characteristic thoughtlessness, dragged us along on his working holiday which happened to be out in the back of beyond in a place where we didn’t speak the language, and in those days it was much rarer for the Norwegians to have the fluent English that they virtually all seem to have now. There was nothing much to do, the place was twenty kilometres from the nearest village, and in any case we didn’t have a car. It wasn’t really walking country, and the countryside was plagued with midges so it wasn’t much fun walking.

I think Mum must have been deadly bored, and that was why she started making a wickerwork doll―simply to have something to do. She gathered blackened skeletons of heather, and from the collection of twigs wove and twisted together the plant material into a rudimentary figure about 18 inches tall. It wasn’t much to look at, but clearly the image of it stuck in my head sufficiently for it to come to mind as I began exploring ideas for a project. Inevitably I’m going to have to reproduce something along similar lines, although what I make might have some additional accoutrements and perhaps fur-fabric paws and eyes made of seashells. We’ll see…

Mick Davies

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Oil On Water Press