A Bird on the Branch of Tomorrow

David Kerekes [DK]: How are you this morning? Have you done anything today you didn’t do yesterday?

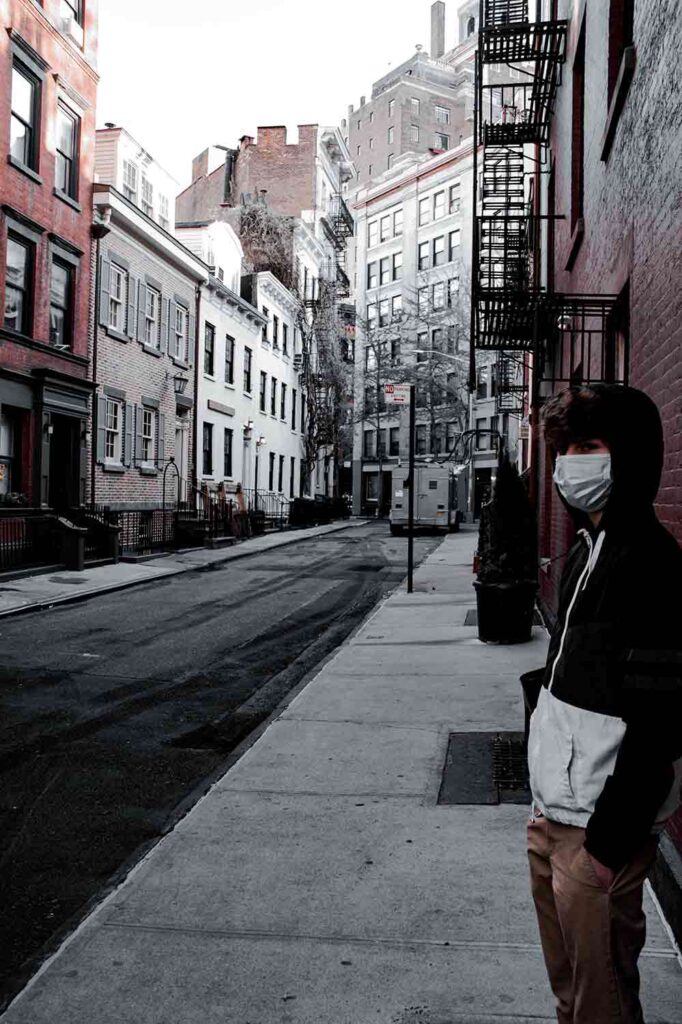

Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee [MFB]: I am alright, thank you. I decided to take a walk in the neighbourhood today. Winters are good for walks. There is a chill in the Delhi air. India is not under lockdown currently, but cases are being reported, and the hospitals are still crowded with Covid19 patients. There are also reports of migrant labourers returning to cities for work. Except health workers, those who provide essential services, and journalists, a lot of people are still working from home. Markets are unevenly open. People are going easy on cafés and restaurants, but they are travelling. My sister who lives in Mumbai took a flight to visit my mother in Kolkata. A journalist friend from Delhi is visiting Assam, and posting pictures of her safari in Kaziranga National Park on Instagram.

DK: About your book: I mentioned some weeks ago that I believed yours was a book that everyone thought they should write. I would add that arguably it is the ‘quintessence’ of popular and unpopular culture, given the curious time in which we are living, which, I think, also answers your question as to why Headpress should add your book to its list. Where do you think a book like The Town Slowly Empties sits in the greater scheme of things? Is it memoir, social commentary… ?

MFB: I think the book, like the subtitle says, is a meditation on life and culture. But the meditation has a diverse focus. It combines personal narrative with reflection on wider social and cultural issues. So the book is part memoir-esque, and part commentary. The book is timely, and yet, like Nietzsche’s Untimely Meditations, I raise questions against certain conventional understanding of the world and the way we think. I would like the book to be seen a provocative testament of our dark and difficult times.

DK: The point at which I decided that I wanted to publish this book was almost immediate, swayed by your discussion of Nietzsche in context of protective mask-wearing. Could you care to choose one of your own favoured passages from the book and give a little background?

MFB: The pleasure of reading Nietzsche is that he is so often, so delightfully counterintuitive. When he says, the word is also a mask he casts a metaphoric doubt on the certainty of language.

One short passage I quite liked while writing, is:

Every era has a last station. Then the train moves backwards, its engine attached to the rear. Our sentences stop making sense. We are sentenced for our language. We were sentenced by our language. Words rolled backwards in our tongue. The era stammered.

This image I draw of a reverse journey can be read differently, depending on the context. For instance, reversal can mean pure regression if it entails the subversion of ethical and democratic values. The lives of nations and people often reach an endpoint from where the wheels of time suddenly seem to flow backwards. It is a time when memory, in a complicated way, catches up with you. Strange things take hold of us. You realise that history, like life, does not move in a straight line.

DK: The narrative covers a period of one month, seamlessly tying together your day-to-day routine with fond (and not so fond) memories, the view from your terrace, news reports from around the world, and drawing comparisons with art and literature. Can you give a little background to your process of writing? What comes first, the idea or the action?

MFB: Between the idea and the act of writing, a process of translation takes place, where perception gets translated into writing. You see, observe, think, consider, react, and then decide to write. Writing is a decision, but not always a purely objective, or rational, one. I believe I was prodded by the ghosts that reside in the eucalyptus tree to write this book. Time dictates us to write.

DK: You say in the book, “Watching ourselves, we are also watching other forms of life.” This is in relation to the threat to human life posed by coronavirus. What do we see when watching nature?

MFB: That is an interesting question. We are always aware of something mysterious and wondrous when we watch nature. Our scientific understanding of what we see does not kill our sense of curiosity. There is a curiosity that is more mysterious and deeper that the curiosity that leads science. Nature is a mirror, but a metaphoric one. There is beauty and danger in creation. We also realise that we exist in relation to nature. Being in any relation demands responsibility. We haven’t behaved responsibly with nature. It’s a relation we can’t, like thoughtless and greedy fools, afford to lose, because our existence depends on it.

DK: I like your description of visiting the barbershop, thwart with deep-rooted concerns but at the same time a liberating experience. In fact much of what I like about the book is this sense of the familiar underscored by issues of class and race and prejudice. Do you have another story of the barbershop, maybe one that is not in the book?

MFB: I just read the short piece, ‘The Presidential Barber’, from The Scandal of the Century and Other Writings, by Gabriel García Márquez. He writes with wit and irony, how exceptional it must have been for Mariano Ospina Pérez (the man who ruled Colombia between 1946 and 1950), to trust his barber, the only man in the country who could “allow himself the democratic liberty of caressing the president’s chin with the sharpened steel of a razor blade.” It reminded me of the boy next door to my home in Assam, asking me once, “Who do you think is most powerful man on earth?” I gave him predictably wrong answers. His triumphant reply: “It’s the barber! He alone can hold everyone by the ears.” Akbar, my childhood barber I mention in the book, often faced the awkward predicament of my father asking him to shorten my hair, while I refused to allow him to do so.

DK: You do a lot of cooking in the book. Would you care to share a culinary tip for cooking in lockdown?

MFB: During the lockdown phase I kept to simple recipes. Since I had to cook daily, I thought it is best to not tire myself out by trying anything elaborate. But it is also necessary to overcome the boredom by being innovative and making simple variations. So if I made fried eggs or sunny side up one day, I would make my version of frittata the next, pouring few eggs over a sautéed mix of onions, garlic, tomatoes, potatoes and Bok Choy. If I cooked fish with mustard seeds and curry leaves one day, I would use onion or cumin seeds the next time, and add coriander leaves. With meat, I usually prefer to cook it fresh, directly frying it with the masala. For a change, I would take recourse to marinating it with curd, garlic and ginger, before pouring it in the fried masala.

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Oil On Water Press