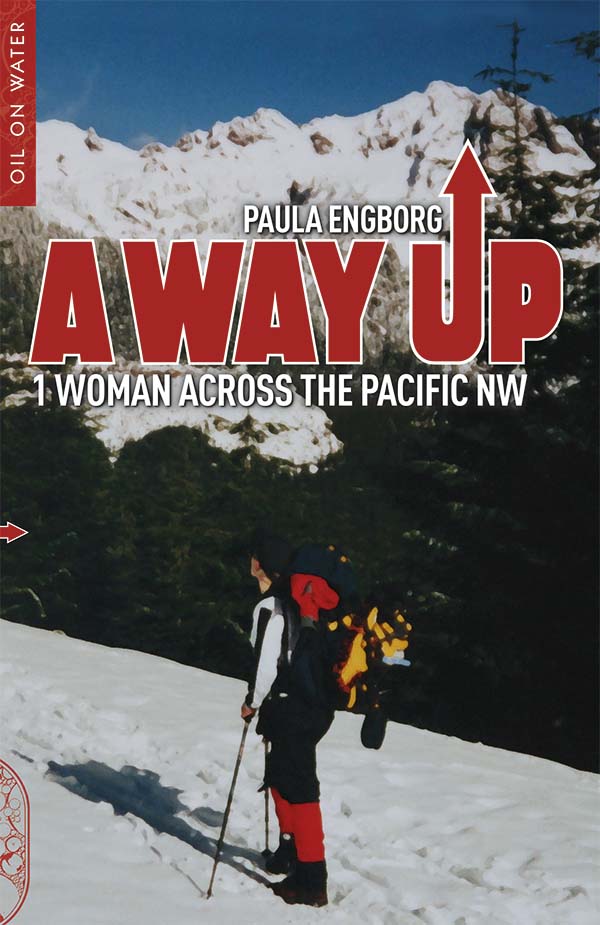

Muscles and mountains. Finding Paula Engborg And A Way Up

SOON, I WILL TURN FORTY. I’m not entirely sure how that’s happened, though it doesn’t feel too awful. Good to draw lines under stuff, and whatnot. If nothing else, it’s probably as good a time as any to do something about the whole exercise thing. A couple of lockdown kettlebell phases aside, too much of my thirties has essentially been inert. It wasn’t always this way; back when I still made an effort, the younger me would have been sniffy at the idea of needing a ‘couch to 5k’ app, but the joke’s on him. Now, I would need to train for three months before I could even attempt a local parkrun. A relentless, if entirely familiar, decade of intense new-parenting, medical setbacks and professional burnout has taken its toll.

In the last few years, I have been fascinated by public figures at the more extreme end of athleticism: ultramarathoners, strongmen, that sort of thing. I don’t think there’s anything sophisticated happening psychologically here: many of these figures have dug deep, undergoing considerable mental and physical transformations in their lives to get to where they are now. When you haven’t been for a decent run in years it can feel like only an extreme overhaul will make a difference. Perhaps there is also something of a vicarious element; you can kid yourself that you are physically capable because you read about it all the time. Maybe that’s how — without naming any names — certain men’s and women’s health magazines have been able to keep going forever, even though each month’s issue looks exactly the same; as long as you know how you could go about sculpting those boulder shoulders, that’s nearly good enough……

That said, there has definitely been a shift in gym culture over the last couple of decades. Fitness is cool, sports gear is fashionable, clean/superfood/high protein diets are well catered-for. Weights are no longer the preserve of the rugby team, hard nuts and bodybuilders; there is a recognition that different people have different goals. It was not always like this. Paula Engborg notes:

‘When I first used a gym about 40 years ago I had a slight build and men scoffed at females who strength trained. Women were considered inferior physically to men. I learned that a fit woman could be stronger than a man. Things are changing. There are more women's sports and it seems it is more acceptable to see women who sport muscular arms, legs and torsos these days’.

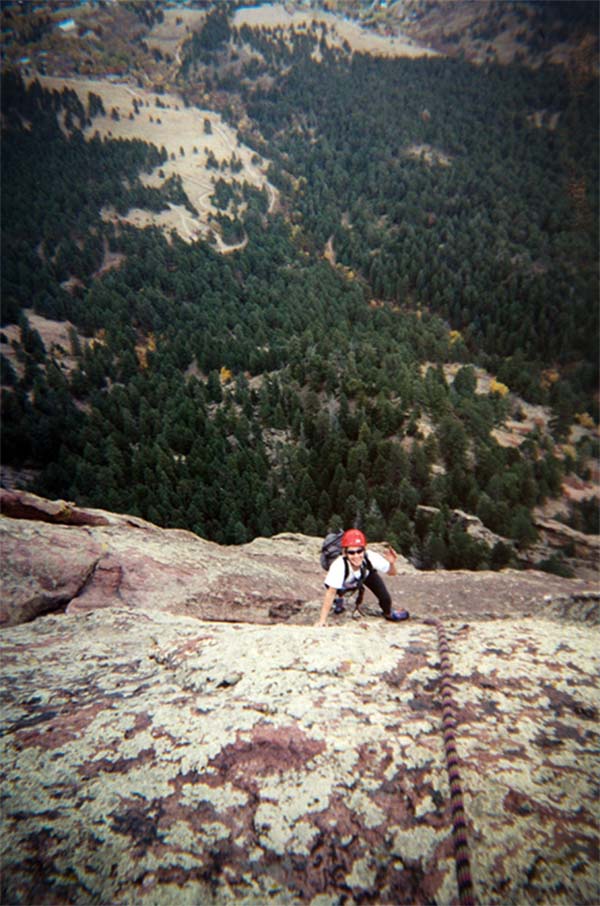

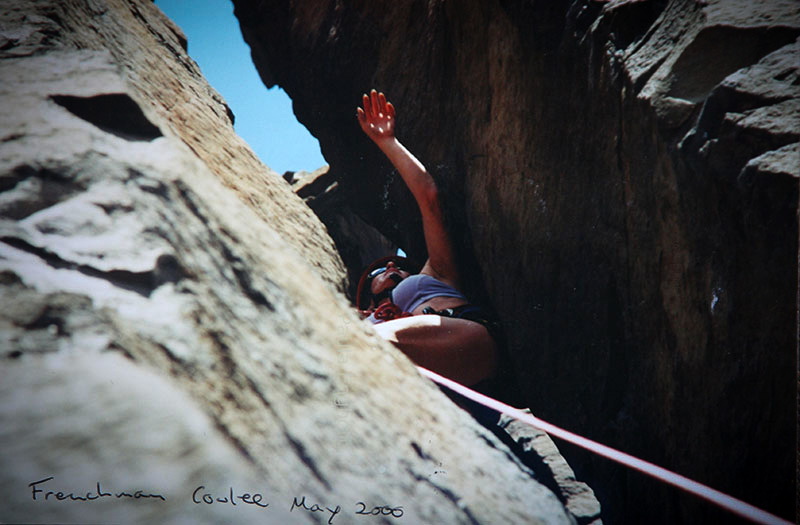

Paula was a personal trainer before she was a climber, and the work she had put in at the gym and elsewhere created a very effective base for taking up a sport which demands incredible strength with no excess bulk. ‘I was occasionally advised not to lift heavy by men in the gym, but I found my strength and aerobic endurance aided me invaluably when I climbed.’ Another defining feature of fitness magazines is the celebrity workout: it is interesting to note that Mark Twight, the trainer behind one of the most notorious Hollywood fitness challenges, the 300 Workout, comes from a climbing background.

The OOWP office isn’t far away from the start of one of the UK Ironman courses. I took the kids to watch it a couple of years ago. We could see the triathletes emerge from the 2.4-mile swim in open water and seamlessly transition to the 112-mile bike phase, after which they would finish the day with a nice little marathon. I wasn’t sure what I was expecting; hordes of flared-nostril alpha figures with 1000-yard stares and adrenaline for days, maybe. Instead, what struck me was how normal most of the competitors looked. Clearly highly conditioned, but otherwise ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Not blogging about it, not making a living from it on social media; just enjoying doing what they do, and clearly have done for a very long time. I doubt many of them would have regarded their achievements that day as exceptional. There will always be someone faster, or something they could have done differently, at every level of competition. When you surround yourself with excellence your perception of excellence rarifies accordingly — not to a false modesty, but a humility in keeping with your context.

I asked Paula about some of the more hair-raising bits of A Way Up. I could understand how, as you’re starting to slide down a frozen mountain, an instinctual self-preservation such as using an ice-pick as a makeshift brake might kick in, but I wondered if such near-misses demanded quite a lot of mental processing after the event. Her response: ‘As for the aftermath of “close calls,” I personally didn’t think much about them. They were part of the climb and problems that occurred due to particular circumstances. I would assume that I wasn’t alone in experiencing danger in the mountains. Having skill, reacting quickly and being observant served me well.’

Becoming acclimatised to the possibility of life-changing injury or death is not the same as underestimating the risks. As with all extreme sports, the serious climber knows what they are getting themselves into (give or take a couple of encounters outlined in A Way Up) and, like the TT motorbike rider or the MMA fighter, there is no room for complacency. ‘Climbing is an adrenaline junkie’s sport. It is a huge rush to make it to the top of a high peak, or a summit fraught with obstacles. Rock climbing is always a thrill when climbing outdoors, because any number of things can go wrong, as they can on a mountain climb. The climb is a dangerous puzzle, unlike any other.’ And there lies a key point. Why climb? Strip it down, and the answer strikes me as being: for the sake of it. The mountain is a puzzle to solve, so let’s solve it. There is a commendable purity in undertaking challenges which we don’t have to do, something which simultaneously captures the absurdity of existence while imbuing it with meaning.

Even as a child, Paula found sanctuary and connection in the outdoors: ‘For me exploring the woods and creeks in Virginia was always a bit of an adventure. I often took different routes and made discoveries like where the deer slept and the wire fence that divided out property from the next and ran across the creek. Such finds stimulated my imagination, simple as they were. I felt free.’ Nowadays, her interests are much less life-threatening than climbing, but no less elevated: ‘I still hike occasionally and enjoy long walks on the beach. I have extensive gardens that require my regular attention, a large home to clean and a husband with a good appetite to feed’. As for me, I’m off to find a way up for myself physically: after all, when you’re starting from the bottom, it’s the only way to go.

Lance Manor

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Oil On Water Press